Reblogged from: http://newblackman.blogspot.com/2013/10/trick-or-treating-while-white-white.html

Reblogged from: http://newblackman.blogspot.com/2013/10/trick-or-treating-while-white-white.html

A four-part documentary by Ivan Dias, entitled Apanhei-te cavaquinho, discusses the influence of the instrument in the music of Brazil, Portugal, Cape Verde, and Hawai’i. The documentaries aired last year on Portuguese television (RTP). I believe that all four episodes are available on YouTube. Sorry, no English subtitles. I will post a review of the documentary soon.

Back in June, my colleague Brian Griffith invited me on his radio show The Humanoid Playlist to talk about the cavaquinho.

The cavaquinho is a small 4-string guitar-like instrument of Portuguese origin. Due to centuries of Portuguese colonialist projects, variants of the instrument exist around the world. Many readers may be familiar with one of these variants, the Hawaiian ukulele.

Portugal

The cavaquinho appears to have emerged in the Minho province (the region north of Porto) Until very recently, the cavaquinho has remained primarily a folkloric instrument closely associated with the traditional music and dance of the region and its largest city, Braga.

The Portuguese cavaquinho is a small instrument about the size of a soprano ukulele (see images). They are usually made with spruce tops (soundboards) and walnut or rosewood back and sides. Unique features include a fingerboard that is flush with the body of the instrument, unlike guitars and the other cavaquinho-derived instruments discussed here which employ a raised fingerboard. It is common to have a separate wood (usually a harder, darker wood such as walnut or rosewood) that asks as a scratch plate to prevent damage to the spruce top.

Portuguese Cavaquinhos

source: http://www.sondart.pt/catalogs/1/catalog_items/713

The Portuguese cavaquinho uses 4 metal strings. Several tunings exist, but a common one is G-G-B-D. The Portuguese cavaquinho is played with the fingers and often uses a strumming technique called “rasgado” which can be seen in the following video:

Brazil

Unlike in Portugal, the cavaquinho plays a prominent role in Brazilian popular music, from choro to forró to samba. The Brazilian cavaquinho is larger than the Portuguese cavaquinho (see image below). Like the Portuguese cavaquinho, the Brazilian instrument uses 4 metal strings. However, the Brazilian tuning is D-G-B-D and in Brazil the cavaquinho is played with a pick. The body is most frequently made of spruce or cedar soundboard with Brazilian rosewood, or maple, back and sides.

This is a video (sorry, no English) that demonstrates the Brazilian cavaquinho nicely, including various rhythms as well as it’s abilities as a solo instrument

Cape Verde

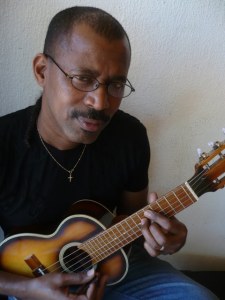

Bau, famous cavaquinista from Cape Verde, with a Cape Verdean cavaquinho.

photo:http://cafemargoso.blogspot.com/2010/06/dos-com-bau.html

The Cape Verdean cavaquinho is larger still than the Brazilian cavaquinho (see photo below) It uses the same tuning as the Brazilian cavaquinho and is also played with a pick. The result is an instrument that sounds very similar to a Brazilian cavaquinho, but often playing Cape Verdean rhythms such as morna and coladeira.

For those interested, here is a link to a rather long (6 mins) video (again, sorry, no English) that illustrates the Cape Verdean cavaquinho. At about 2 mins the video illustrates several cavaquinhos in various stages of the construction process. At 3mins 9 seconds, the video illustrates various rhythms from Cape Verde.

Here is an image which illustrates the relative size differences of the instruments.

From left to right: Portuguese cavaquinho, Brazilian cavaquinho, a cavaquinho from the island of St. Antão in Cape Verde (not very common) and the standard (note, much larger) Cape Verdean cavaquinho on far right.

photo: http://www.atlasofpluckedinstruments.com

Hawai’i

The Portuguese cavaquinho arrived on the Portuguese island of Madeira by 1854 and became the local regional variants known as “braguinha” or “machete,” as well as a larger rajão. In 1876, immigrants from Madeira arrived in Hawai’i, bringing their instruments with them, and soon after they began making instruments from beautiful Hawaiian koa wood. These developed into the ukulele. This video illustrates the unique sound or timbre of the ukulele’s nylon strings and koa wood:

Indonesia

In Indonesia the cavaquinho developed into two separate highly specialized instruments that play interlocking figures together in kroncong music. There is the cak which features 4 metal strings in 3 courses, and the cuk which is slightly larger and has 3 nylon strings.

Cak (l) and Cuk (r)

Photo: http://www.atlasofstringinstruments.com

The cuk plays arpeggios while the cak strums chords, as demonstrated in the following video:

I am interested in issues of cultural ownership and cultural appropriation, white privilege, and how these impact cultural citizenship practices for Black people in the Americas. And as I think through these complex issues, I’ve found many of the response to Miley Cyrus’s VMA performance to be extremely helpful and right on. Below I’ve posted links to just a few of them.

http://groupthink.jezebel.com/solidarity-is-for-miley-cyrus-1203666732

http://groupthink.jezebel.com/dear-miley-keep-your-fucking-hands-to-yourself-1201998015

I also like to think about this issue (Miley) in conjunction with other events that illustrate how white privilege works to permeate everything and remove race from the discussion. See this fantastic piece by Jamilah Lemieux:

http://www.ebony.com/news-views/i-guess-you-really-aint-sht-questlove-303#axzz2aTK1Pwmh